My father Yim Mau-Kun is known to many as an oil painter. And indeed, his oil paintings are classical in style; if you were to see one of his paintings such as Christina on public display in the US or Europe, you would probably never have thought it’s the work of a Chinese artist. Trained in the 1950s in Mainland China, he was heavily influenced by the Russian school of Realism. His writings and lectures often have reference to 19th century masters such as Valentin Serov or Issac Levitan.

However, my earliest memory of his painting is Jiao Na, a Chinese ink wash painting of a character in a book of Chinese folklore and ghost stories (Liaozhai). I remember this painting hanging in the tiny living room (9 square meters) of our small one bed-room dorm in Zhaoqing, Guangdong Province, China. To the 5-year old me at the time, Jian Na was the most beautiful girl in the world, the equivalent of Elsa to my 4-year old daughter. My father was working as a theater designer for a regional theater troupe after graduating from the Guangzhou Academy of Arts in 1965. Theater design at the time involved mostly painting backdrops which, according to my father, afforded the opportunity to improve his landscape painting skill. At night, he would go to his best friend and Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts classmate Lin Fengsu’s (well-known Chinese ink wash painter) place to practice Chinese ink wash paintings. Jiao Na is one of paintings produced at the time. In his writings and lectures, my father would often refer to Chinese ink wash painting techniques or principles such as the pursuit of spirit and state of mind instead of exact likeness. For example, if you’re painting flowers, the goal is to convey the freshness and fragrance instead of an exact likeness. Additionally, Chinese ink wash paintings often have a blank or light backdrop to convey a Zen-like sentiment.

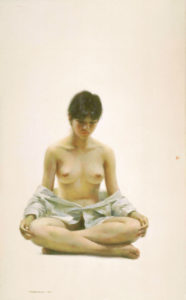

So, for me, the most fascinating part about my father’s art is when the paintings bear visible marks from both of these traditions – Western classical oil painting and Chinese ink washing painting such as Florist and Untitled. Florist is a line drawing done on Xuan paper (or rice paper). My father used Chinese line painting techniques but the figure reflects proper perspective and proportions which are characteristics of the Realist painting tradition of the west. In Untitled, although it’s a Western style human figure painting, the model assumes a seemingly meditative pose and the backdrop is intentionally left blank to embody form and emptiness in the Zen Buddhist style.

Another form of combining West and East traditions by my father is when he uses Western oil painting techniques to depict characters in Chinese historical events or culture. Two examples of this are Death of Concubine Yang and Xuanzang. Concubine Yang (Yang Guifei) is best known for her love story with Emperor Xuanzong in the 8th century. But my father chose to depict the moment right after she was ordered to be executed by the emperor under the pressure of mutiny. The tranquility and sadness in the Buddhist shrine where Concubine Yang was hanged stands in stark contrast with the tumultuous, rebellious imperial guards in the distance, embodied by the torch light which can be seen through the window in the backdrop. Eunuch Gao Lishi and General Chen Xuanli look on with a stone face. Yang’s maid and close friend A Man is weeping bitterly. The mirror on the floor has a reflection of Yang’s face and symbolizes the Chinese saying “flower in the mirror, moon in the water” which is an analogy of fleeting youth and beauty. How this idea came to him, my father said he doesn’t recall. But he is drawn to moments in history with intense emotion and drama such as the aftermath of the death of Yang Guifei and the long night depicted in Guangxu and Consort Zhen before the defeat of the 100 Day Reform towards the end of the Manchurian reign in China, a turbulent time when China struggled to survive against imperialism.

As to the painting Xuanzang it’s not necessary a depiction of intense emotion and drama. Xuanzang is both a principal character in Chinese mythology novel Journey to the West (Monkey King) and a historical character who ventured to India on a seventeen-year journey to bring back Buddhist texts to China in the 7th century. Although my father has never explicitly said why he wanted to paint Xuanzang other than being drawn to the character by his perseverance and courage, personally I think this is a depiction of his own art journey. In the age of Photoshop, social media and big data, classical realistic painting is not very fashionable. Classical drawing training is scanty in art programs. Few people have the patience to spend years to hone drawing and painting skills. And many of his friends and classmates from the Guangzhou Academy of Fine Arts quit painting and went into business. It’s a lonely journey to be sure, but it is one on which he perseveres and never looks back. In his artist statement, he says, “Painting to me is an enjoyment. It is also endless pursuit of artistic achievement. My painting and teaching career has spanned five decades, and I’m continuously experimenting with new ways of expression and approaches for realistic art. I am elated when I make a new discovery.”